By Esaa Mohammad Sabti Samarah

By Lisa Schelbe, PhD

March 17, 2022

I(Esaa) don’t care for the profile of social workers, and those who help others, as heroes without capes. Heroes are infallible, superhuman, and often have very little in the way of a personal life. Me, I’m fallible, I get overwhelmed, and I enjoy having a personal life. This aversion to adopting a superhero persona doesn’t mean I don’t want to help people, because I do. I think most of us do. I get overwhelmed sometimes and need to refocus.

When I read this article about how social workers can and should address dyslexia, I thought “Of course! This makes sense!” But soon the thoughts of “How can I and others who are already doing so much do one more thing? We are not superheroes!” I decided to work with one of the authors (Lisa) to translate the information for social workers (and others) who are working with young people involved in systems of care who are parenting or pregnant.

Whenever I get overwhelmed, I channel the words of a cherished mentor who would always implore me to “go back to the basics” and “focus on what we know.” In her honor we are going to do just that.

Reading is fundamental

The United Nations has identified literacy as a basic human right and an essential component to sustainable development across the world. Reading provides benefits that extend beyond the classroom. Reading ability is associated with positive outcomes in later life including physical health, mental health, longevity, and income. It is not a stretch then to say that reading is a matter of social justice and any barrier to reading is a social justice issue that requires our attention.

Barriers to reading are especially relevant for people who are considered part of vulnerable populations and underrepresented communities because barriers to reading intensify educational challenges that may already exist and can make their lives more difficult. Young people involved in systems of care, including those who are parents, may be especially at risk for reading obstacles (because of structural barriers due to poverty, exposure to trauma, and system involvement).

Dyslexia: An Obstacle to Literacy

A barrier to literacy is dyslexia. Dyslexia, the most common learning disability, makes word recognition, spelling, and verbal expression difficult. School is more challenging for children with dyslexia as they have a difficult time with reading and comprehension. An estimated 5-17% of children have dyslexia.

The negative impacts of dyslexia can be mitigated if identified and treated early; however, many children remain undiagnosed. Early screening for dyslexia is not universally available to all children. Children who are Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) or who live in poverty are more likely to remain undiagnosed than their peers. This limits their ability to access time-sensitive interventions.

Children miss out on learning opportunities when dyslexia is not identified and addressed. Learning challenges due to dyslexia in school can impact a child’s wellbeing including their mental health and behavior. A negative impact on long-term social health outcomes can be observed well into adulthood when these issues persist. Literacy is an important precursor to educational attainment and is predictive of academic success. Identifying and treating dyslexia early is essential to closing the education gap.

Literacy is an important protective factor for young parents involved in systems of care and their children. It is central to education. Literacy is an important protective factor that helps students significantly improve their later life outcomes.

Do We Need to Address Dyslexia? (We are already overwhelmed!)

With the understanding that social workers and others in helping professions are not cape-wearing heroes, let’s talk about why those working with young parents involved in systems of care are positioned to address dyslexia.

Social workers and other helping professionals working with young parents involved in systems of care are uniquely qualified to connect young people and their children with services that build on individual and communal strengths. Additionally, social workers are particularly equipped to address dyslexia as a social justice issue due to skills and relationships with young parents. Helping professionals often have prolonged contact with young parents, their children, and an understanding of their needs. Social workers are perfectly positioned to Screen, Refer, Educate, and Advocate for Children (SEARCh) to address dyslexia. See an infographic summarizing this here.

SEARCh to Address Dyslexia

Screen and Identify

Social workers are often tasked with completing assessments for those they serve. Through collecting biopsychosocial information from young parents they serve, social workers make sure the young parents’ and their children’s needs are being met. Social workers should incorporate questions related to reading proficiency and dyslexia during these moments. Dyslexia is heritable which means specific questions about reading for young parent involved in systems of care can help identify potential barriers to reading for their children. Universal screening for reading problems among children and parents in this population can help ensure that children with dyslexia don’t unknowingly fall through the cracks.

Educate

Social workers have a responsibility to educate families, children, and communities about the importance of literacy. Information about dyslexia should be shared. Children, parents, and the community should be aware that dyslexia exists and its impact can be mitigated.

Referrals for Intervention

Social workers should make referrals for interventions and further assessment when risk for dyslexia is identified. This involves establishing and maintaining connections with professionals in the community who are trained to address the unique needs of dyslexia.

Advocate for Children

Social workers must advocate for universal screening and early intervention for dyslexia. Those who are identified as at risk for dyslexia have the right to have their specific needs addressed by reading specialists and other helping professionals as early as possible.

Social Work is Social Justice

As helping professionals, we play an important role not only in identifying social justice issues but also addressing them. We may feel overwhelmed; however, we can’t forget the basics. We must be part of solutions that are both reasonable and impactful for the young parents, their children, and the communities we serve. The benefits of literacy extend far into future generations. Addressing dyslexia can address the education gap and promote better social health outcomes. By doing so, we will make a difference in the world—and no cape is required.

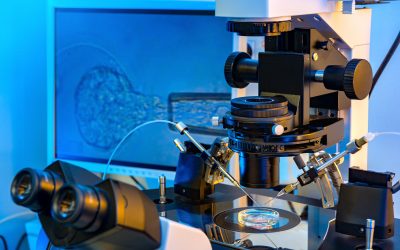

PHOTO CREDIT: twinsterphoto on Adobe Stock

Esaa Mohammad Sabti Samarah is a doctoral student at the Florida State University College of Social Work. Although he has never worn a cape, he does quite enjoy the flying sensation that comes with riding waves. Surfing with his little sister (pictured) and nieces are his most cherished memories and greatest joy. Read more about Esaa Mohammad.

Lisa Schelbe is a non-cape wearing Associate Professor at the Florida State University College of Social Work. If she were a superhero, she would definitely want to have the ability to fly (and breathe underwater, become invisible, see through walls, and write perfect first drafts of papers). Read more about Lisa Schelbe.