6 Storytelling Lessons Learned while Creating the Casey Young Parents Stories.

By Patricia Natalie, MA

June 8, 2023

When I first joined Healthy Teen Network in March 2022, my first project was to “create stories about young parents that can affect policy change.”

Wow, I thought, a huge undertaking.

I had learned about the power of storytelling in my graduate program, and I have seen the impact of personal stories in the advocacy space firsthand, but I had always been the reader, watcher, and listener of these stories. However, to be on the other side, to turn real-life stories with all their nuances and complexities, into something that can tangibly improve policies and impact governance? I had to admit—I was slightly paralyzed.

We started the project by interviewing a caring, big-hearted young parent named Bella. Their lived experience as a young mother navigating homelessness was extremely layered and their challenges, real and present. At our first meeting, they called us from their car, struggling not to get evicted from their current housing. They powerfully and vulnerably shared their journey, challenges, and hopes and dreams with us. We were left speechless, listening to how unjust, discriminatory, homophobic, and broken the care system is.

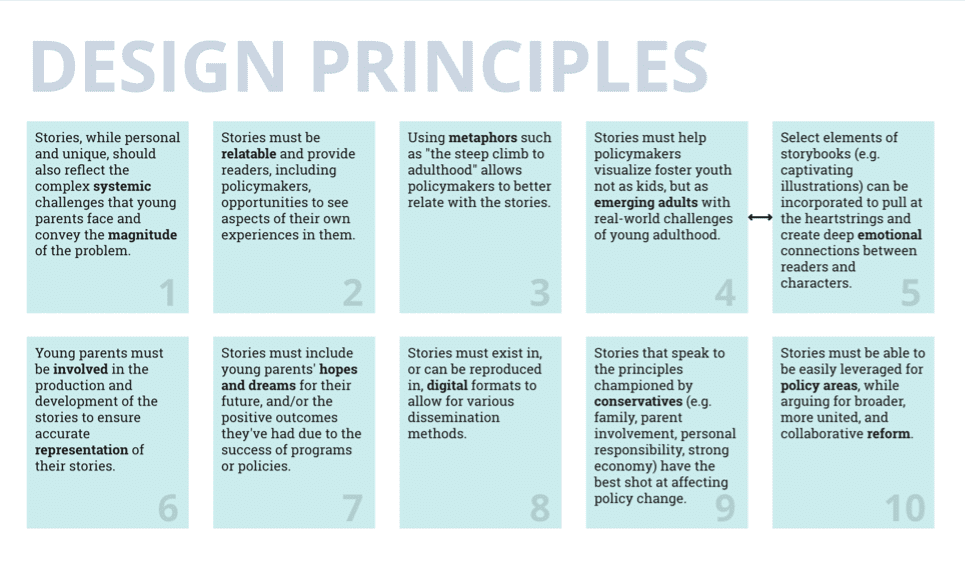

We turned to human-centered design to guide us, as we attempted to package such complex stories into digestible content in an accessible format, so that policymakers and advocates could use these stories to push for services that better support young parents and foster youth. To help us create these stories, we dove deep into academic research, storytelling tool kits, policy frameworks, and language strategies—all while relying on the honest feedback from our young parents, our on-the-ground advocacy partners, and our staff to drive our work.

We learned many lessons throughout the process, but here are six that I value the most from developing these stories.

Don’t expect to change the world with a single story.

This may sound obvious, but learning to temper my expectations, and keeping this in the back of my head, kept me going. The aim for this project, and for most stories for that matter, is to open minds and hearts, and to start conversations. When conversations happen, culture can start to shift, and that’s when policies can begin to change. As Marya Bangee said at the SSIR’s Nonprofit Management Institute, “Cultural change precedes policy change. When we neglect the cultural element, our political wins are more vulnerable.”

Be flexible with structure.

Every story has a beginning, a middle, and an end; a plot, a conflict, and a resolution. There are different ways to “arrange” these building blocks into a story, each resulting in a different narrative. There’s the famous Pixar framework, the Hero’s journey, Rags to Riches—the list goes on. Our team spent some time plotting our young parents’ stories using these tried-and-true frameworks, iterating on various permutations to find the most compelling narrative. In the end, while the story frameworks helped get us started, we learned that there is no perfect story arc. In true human-centered design fashion, we let the process guide us, and we created a final narrative that didn’t neatly fall into these pre-existing story structures. And that’s 100% okay.

Trust the process, while knowing when to pivot.

The core principle of the human-centered design approach is to place the people we are designing with at the center of the process. While deciding on the format of these young parents’ stories, we had a hunch that a traditional storybook, in its physical format, would allow readers to reminisce their childhood experience and be connected on a deeper level with the young parents in the stories. However, after gaining more insights from our young parents, we discovered that a digital format would be most accessible, desirable, and viable for both young parents and policy advocates. We trusted the process, used these Design Principles as our north stars, and were able to pivot from our early-stage prototypes. (After all, prototypes serve that exact purpose of ensuring that our products are usable!)

Aim for the heart.

Some of the best stories out there allow us to tap into the deepest parts of ourselves, make meaning in our own lives, and empathize with people we’ve never met. Focus on the emotional aspect, yet use emotions with intention. Don’t use sadness and fear tactic narratives as the end-all-be-all—we feel so much more than sadness. As Samantha Wright and Annie Neimand said, ”different emotions lead people to do different things.” Finding ways for our audience to identify with a character in our stories can make it more meaningful.

Leave things between the lines.

We don’t have to try to include every single detail, insight, challenge, systemic factor, and call-to-action in our narrative. Some things are better left unsaid—there’s an art to leaving parts of a story open for the audience’s interpretation, allowing them to ‘fill in the blanks’ and participate in the creation of the story. “You don’t have to tell the reader what it all means. You don’t have to raise difficult questions. The people reading, watching, or hearing your story will find plenty to think about if your story is crafted carefully,” said Dinty Moore in his book The Truth of the Matter: The Art and Craft in Creative Nonfiction. Moreover, the use of powerful imagery can also elaborate more on what can’t be said in words.

As designers, facilitators, and professionals, we owe it to young people to cultivate a safe and healing-centered, trauma-informed environment for them to share their story, which means always prioritizing their well-being and ensuring that they have agency over their own narrative.

Sharing stories can be healing in and of itself

In addition to the impact that stories can create for the audience, stories can also be healing for the storyteller. There are numerous scientific and anecdotal evidences of the healing power of sharing and taking control of your narrative. “Storytelling allows a space for one to empathize with [themselves], as a step to gradually empathizing and finding a verse to add with the world around them…Young people are shifting mindsets away from being passive consumers of a world in constant change, and discovering their capacities for being active creators of a new narrative of the self,” said Mohsin Mohi Ud Din, Founder of #MeWeSyria. As designers, facilitators, and professionals, we owe it to young people to cultivate a safe and healing-centered, trauma-informed environment for them to share their story, which means always prioritizing their well–being and ensuring that they have agency over their own narrative.

I think of Bella, Lucero, and Carmen’s stories while moving through my work and my life. I think of their hopes and dreams—for themselves and for other young parents—and how the current systems get in the way of achieving their dreams. I hope that their stories touch the hearts and lives of other advocates in a way that they did mine.

To learn more about their stories, visit the Young Parents Stories.

PHOTO CREDIT: Illustration by Tony Midi

Patricia is a curious learner who loves to ask questions and find patterns. If you look closer, you might see a literal light bulb above Patricia’s head when she sees a connection or realizes something in her research. Patricia loves using those insights to co-create changes—big or small—that make the world a better place. Having grown up in three different countries, Patricia sees the world differently and always makes time for travel. In her free time, Patricia can be found browsing offbeat Airbnbs or walking her sweet, black cat on a leash (yep—it's one of Patricia’s proudest accomplishments). Read more about Patricia.