Learn how Child Trends identified scammers who did not meet the eligibility criteria for their online study.

By Elizabeth Cook, Makedah Johnson, and Jennifer Manlove, Child Trends

July 13, 2018

Health interventions have increasingly incorporated technology components, sometimes even using technology to recruit participants. Technology-based studies present unique advantages, such as being cost-efficient, providing researchers with a large recruitment pool, and allowing participants to remain anonymous.

However, a challenge that accompanies this form of recruitment is ensuring that participants are who they claim to be.

However, a challenge that accompanies this form of recruitment is ensuring that participants are who they claim to be.

Our evaluation team at Child Trends addressed this issue during the past three years as we evaluated a strictly technology-based intervention through the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Adolescent Health Teen Pregnancy Prevention Program. The intervention, Pulse, is a sexual and reproductive health app developed by Healthy Teen Network and MetaMedia Training International.

For this evaluation study, we never came into direct contact with participants since we used social media ads to recruit our sample of young, primarily black and Latinx women ages 18-20. Participants took part in the intervention by looking at the app whenever it was convenient for them. We used pre-programmed text messages to reinforce the app’s content and remind participants to go back to the app, but we never communicated with them unless there was a problem, which was rare.

The Pulse study encouraged enrollment by offering incentives: $25 to take the baseline survey and enroll in the study and another $20 for taking a follow-up survey. While these incentives are comparable to other studies, they can encourage both eligible and ineligible participants to join the study. We know from other similar studies that identifying suspicious accounts is necessary but can be a major challenge. To address this issue, our team developed procedures to make sure we only enrolled people who actually met our recruitment criteria, not just those who said they did.

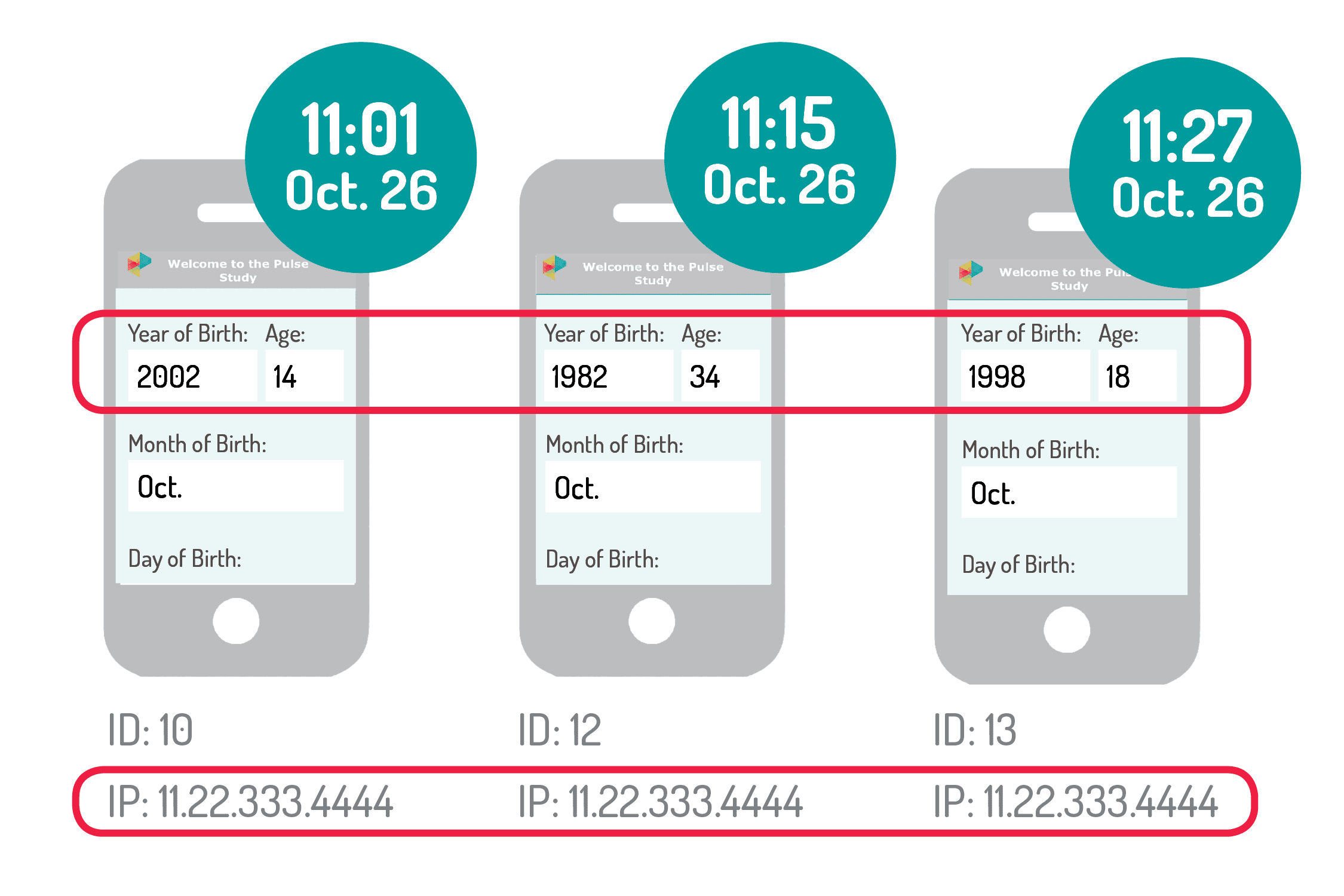

We defined “scammers” as people who didn’t meet our study’s eligibility criteria the first time they tried to take our electronic screener but then eventually met the criteria after trying the screener again. The hypothetical example below shows a scammer who used the same IP address three times but changed their age each time.

Example of a scammer who used the same IP address but changed their age.

At first, the person was too old to be in our study (35 years). On the second attempt, this person changed their birth year from 1982 to 2002, which made them too young for our study (15 years). On the third attempt, the person changed their birth year to 1998 and passed the screener. According to our protocol, the third attempt would have been removed from our sample.

We defined “duplicates” as people who met the eligibility criteria on their first attempt but then tried to enroll in the study again.

We defined “duplicates” as people who met the eligibility criteria on their first attempt but then tried to enroll in the study again. We assumed in these cases that the first attempt reflected the person’s true identity, so we removed the subsequent attempt(s) but kept the first one in our sample. Not all duplicates were necessarily malicious. Because the study enrollment period lasted for almost a year, we recognize that some participants from earlier in the study did not recognize that they were enrolling in the same study twice. Other duplicate accounts were due to participant challenges with accessing the app once they enrolled (so they enrolled again for access).

So how did we identify these people? We set up detailed protocols to address each type of situation, and several times a week, in collaboration with staff from our data collection partner (Ewald & Wasserman Research Consultants), reviewed data from our enrollment system to identify users with similar information on key topics.

- IP address

- Name

- Email address

- Telephone numbers

- Physical address

Once we identified scammers, we notified them that they were being removed from the study due to their ineligible attempt. We deactivated the scammer and duplicate app accounts, so they would not be able to log in again.

This process was challenging for a couple of reasons. First, we didn’t have software that could automatically identify scammers and duplicates in real time. It took a lot of time for our staff to do this process several times a week, and it became more complicated as we recruited more people. Another challenge was that it was impossible to know if we were occasionally dropping some valid participants that we didn’t want to drop. To avoid this as much as possible, we tried to make our screener difficult to scam in the first place. One way we did this was by structuring screener questions, so that it was difficult to determine what the right answer was if you didn’t get it right the first time.

Despite the challenges of identifying and removing scammers and duplicates, it was a critically important part of ensuring that we included only eligible participants in our sample. Of the 1,588 participants who met the screener eligibility criteria and went on to complete the enrollment process, 18 percent (284) were identified as scammers (25) or duplicates (259) and removed from the sample. Our final sample of 1,304 participants is well-powered to conduct evaluation analyses.

Child Trends is the nation’s leading research organization focused exclusively on improving the lives of children and youth, especially those who are most vulnerable. They work to ensure that all kids thrive by conducting independent research and partnering with practitioners and policymakers to apply that knowledge. They believe that programs and policies that serve children are most effective when they are informed by data and evidence and grounded in deep knowledge of child and youth development. Read more.